Trump Once Proposed Building a Castle on Madison Avenue

Compiling a definitive list of what Donald Trump has not managed to accomplish, despite his self-proclaimed status as a master developer and dealmaker, is a task best left to a future historian. One project has recently made news: the skyscraper Trump sought to build in Moscow, a long-held dream he pursued throughout the 2016 campaign despite his repeated assurances that he had no business ventures in Russia. The nature of that potential deal, the vast sums of money behind it, the influence he brought to bear on the Russians and they on him—all of this is beginning to clarify, like a photographic print in the developing tray. The deal and the possible quid pro quos involved are a major focus of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation.

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

The Moscow tower, which at 100 stories would have been the tallest building in Europe, was but the latest attempt by Donald Trump to leave behind a skyline-altering legacy. His career is marked by plans for major projects that never came to pass—arguably to posterity’s benefit. Herewith, a quick summary of what never happened.

Trump Castle, Madison Avenue

Born: 1983. Died: 1984.

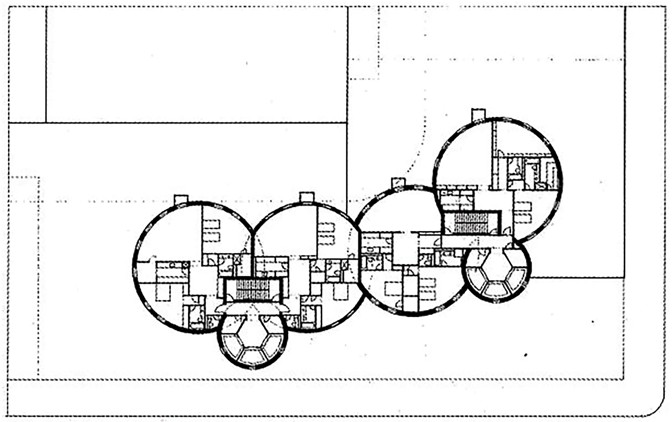

“Lunacy.” That was real-estate brokers’ contemporaneous description of Trump’s intended follow-up to his flagship Trump Tower, on Fifth Avenue in New York: a 60-story luxury residential complex, designed by the renowned if erratic Philip Johnson to mimic a medieval castle. The project included six cylindrical towers with crenellated tops, spires, and gold-leaf adornment, plus, at street level, a drawbridge and a moat. Announced in 1983 for a site on Madison Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, it was to be called—inevitably—Trump Castle. Prudential Insurance had bought the land, on which sat an eight-story building, in 1981. The company then brought Trump into the project and gave him a 49 percent stake for free because, as a Prudential executive later explained, “his name had magic in it.” While Johnson’s castle design was, as architecture, a world away from Trump Tower’s black-glass slickness, Trump was enthusiastic. As “a source close to the developer”—probably Trump himself—told New York magazine, “After Donald did Trump Tower, there’s not a lot left for him to do in this business, so he just wants to do something great.”

The partnership between the 37-year-old developer and the 77-year-old architect was not as unlikely as one might think, given their shared egotism and love of the limelight. “These guys are hot!” Trump told The New York Times, referring to Johnson and his partner, John Burgee, who had just goosed Manhattan’s skyline with the showy postmodernism of the AT&T building. Johnson returned the compliment, declaring, “Trump is mad and wonderful.”

No models or drawings of Johnson and Burgee’s design appear to have been made public at the time, though the architects’ campy, turreted office building at 33 Maiden Lane, in downtown Manhattan, hints at the glory that might have been Trump Castle. The project fell apart amid rising real-estate prices and increasing competition in the luxury-apartment market. Trump’s spokesman “John Barron”—most assuredly Trump himself—explained to New York that Trump Castle had become “just too expensive” and that the developer had grown impatient with the approvals process. Trump still got mileage out of the idea, buying a casino from Hilton Hotels and christening it Trump’s Castle in 1985. It filed for bankruptcy in 1992.

World’s Tallest Building, East River

Born: 1984. Died: 1984.

Trump and Prudential gave up on Trump Castle in May 1984. Two months later, the Metropolitan Transit Authority unveiled development proposals for a site on Columbus Circle that it co-owned with New York City. One plan called for a 130-story tower—which at the time would have been the world’s tallest building, soaring 20 stories above Chicago’s Sears Tower. Headlines ensued, and if you were a brash young developer who had just lost the chance to build his own castle, you might have taken this as a slap in the face.

Two weeks after the MTA’s announcement, Trump snatched headlines back, declaring that he wanted to build an even taller world’s tallest building on land reclaimed from the East River, just south of the South Street Seaport. “New York City deserves to have the tallest and greatest building in the world,” Trump told the Times. “From the standpoints of light and air and density, this”—the East River site—“is the only location where that building could be built.” Trump’s vague proposal envisioned a combination of offices, a 40-story “luxury” hotel, and on top, 50 stories’ worth of “super luxury” apartments. In Trump’s mind, the “world’s tallest” designation was both a raison d’être and a shield: “I have not had one negative comment,” Trump would tell the Times. “If I had said 70 stories, 60 stories, everybody would have said, ‘Let’s block it.’ ”

That remark about no negative comments? It didn’t hold. Two months after the announcement, Trump filed a $500 million libel suit against the Chicago Tribune and its architecture critic, Paul Gapp, over a critique that had dismissed Trump’s proposed building as “one of the silliest things anyone could inflict on New York.” The Tribune article was enlivened by an amusingly crude (or, from Trump’s perspective, “false and defamatory”) photo illustration of a drab, Lego-like skyscraper plunked down on the East River and listing toward Brooklyn, as if built on a raft. Trump’s complaint claimed that the bad publicity had “torpedoed” his plans—crediting the Chicago press with more influence than it typically wields in Manhattan. A year later, a judge dismissed the suit. In the end, the East River site was left to the fishes.

Two More World’s Tallest Buildings, Columbus Circle

Born: 1985. Died: 1985.

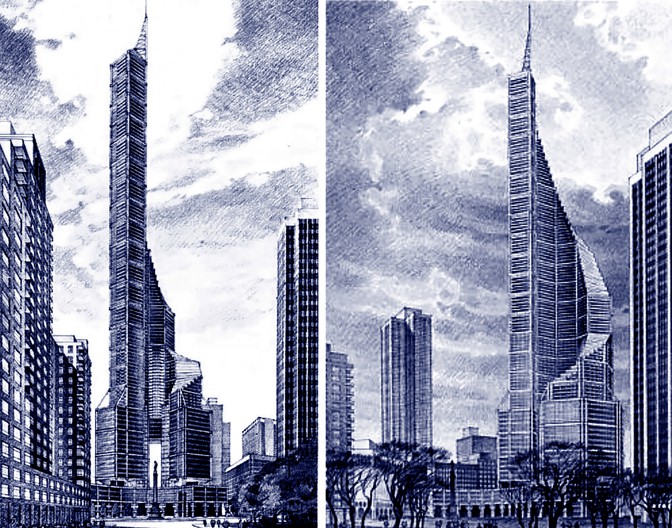

After declaring Columbus Circle all wrong for a 130-story tower built by someone else, Trump was back with two even loftier proposals for world’s tallest buildings on the same site, accompanied by renderings meant to dazzle the public’s eye (and perhaps preempt the Chicago Tribune’s art department). At 137 stories, the taller of the two buildings was a 10-sided telescoping tower designed by Eli Attia, the Israeli American architect arguably best known for his work on the Crystal Cathedral, in Southern California. At a widely covered May 1985 preview, New York City Mayor Edward Koch likened the Attia design to a “Flash Gordon building.” Whether this was intended as a compliment is unclear. In the Times, the architecture critic Paul Goldberger was not ambiguous: “It looks like storybook pictures of the Tower of Babel.” The second, smaller (135-story) design was by the German American architect Helmut Jahn, and what it lacked in height it compensated for with ostentation. It resembled a sky-high staircase made of glass. “It’s the Busby Berkeley building!” Koch proclaimed. “It looks like you could dance down the steps!” This was meant as a compliment.

Trump’s proposals lost out to one from a group headed by Mortimer B. Zuckerman (the owner of The Atlantic at the time). That design, by Moshe Safdie, topped out at about 70 stories. It, too, was never built, sidelined by the 1987 stock-market crash. Today, the site is home to the Lilliputian 55-story Time Warner Center.

Television City, Upper West Side

Born: 1985. Died: 1994.

“Make New York great again!” could have served as the slogan for the mixed-use project Trump announced in November 1985, only months after his Columbus Circle plans had been rejected. Trump’s most ambitious project ever called for half a dozen 76-story apartment towers, retail spaces, parks, and a new studio for NBC, which was then threatening to leave its longtime Rockefeller Center home. Thus the project’s name, Television City, which sounded dated even in the 1980s.

Television City was introduced (with a World of Tomorrow–style model) at a press conference that made national news. Its centerpiece was to be Trump’s fourth go at a world’s tallest building: a 150-story spire that would have cast a morning shadow all the way across the Hudson River to New Jersey. New York needed to be home to the world’s tallest building, Trump insisted. “This is to be a great monument, majestic,” he declared. “It shouldn’t be built in Denmark.”

Trump’s site was the old Penn Central rail yards, 77 dormant acres that stretched along the Hudson from 59th Street to 72nd Street—for years the city’s most extensive vacant lot and a graveyard for real-estate dreams, given the Upper West Side’s history of anti-growth activism. Trump had paid $115 million for the site in 1985. Again he called on Helmut Jahn, who designed both the spire and the residential towers. In interviews, Jahn likened the central tower to an obelisk, investing it with pharaonic, Trump-flattering splendor. Time magazine conceded that the overall plan had “a certain breathtaking screwball grandeur,” but one community activist, apparently irked by its grandiosity and its separation from the surrounding urban grid, dismissed it as “a veritable walled city.” To be fair, it had no moat or drawbridge.

Trump’s ambitions for Television City ran aground after he got into a fight with Ed Koch over tax abatements—a conflict that, given the two needily splenetic temperaments involved, exploded into a tabloid spectacle. Trump dismissed the mayor as a “moron” with “no talent and only moderate intelligence.” Koch refined his critique of Trump’s alleged greed to a memorable “Piggy, piggy, piggy.” Trump then lost his prospective anchor tenant when NBC decided that it would stay put in Rockefeller Center after all; generous tax breaks from the city helped. Television City’s final death rattle came in 1994, when Trump’s enormous debts forced him to sell the rail-yards property for about $20 million less than he had paid for it.

World’s Tallest Building, Wilshire Boulevard

Born: 1990. Died: 1992.

Just two weeks into the new decade, Trump announced his latest swing for the fences: a 125-story tower, yet again the world’s tallest, to replace the shuttered Ambassador Hotel, in Los Angeles. Trump, the public face of a group of investors, held a Saturday press conference at the Wilshire Boulevard site, joined by Mayor Tom Bradley and the local city-council member, neither of whom evinced much enthusiasm for Trump’s plan—a “world class” mix of apartments, retail and office space, and a new hotel. The Ambassador was most famously where Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated, in 1968; as a Los Angeles Times columnist pointed out, the hotel bar, the scene of Trump’s press conference, was also where, in The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman’s Benjamin Braddock and Anne Bancroft’s Mrs. Robinson met for a drink before consummating their awkward, asymmetric, ultimately pathetic relationship.

Trump was soon feuding with Bradley (who decided the plan was “inappropriate for the area”). Another antagonist was the Los Angeles Unified School District, which hoped to build a high school on the site. With negotiations bogged down, Trump hired the L.A. architectural firm Johnson Fain and Pereira to provide a design. “Donald Trump used to call us the Die Hard guys,” Scott Johnson, a partner at the firm, later recalled, referring to its work on the flashy Century City office tower that had been used in the film. The design done for Trump looked like a display of Art Deco lipstick cases—it was later featured on the front page of the Los Angeles Times (and can still be found on the Chinese-language version of the firm’s website). But the school district had a powerful ally: Assemblywoman Maxine Waters, the future representative from California (and future target of derogatory presidential tweets), who helped find funding for the high school. Trump, fighting off creditors elsewhere, threw in the towel.

New York Stock Exchange Tower, Lower Manhattan

Born: 1996. Died: Circa 1998.

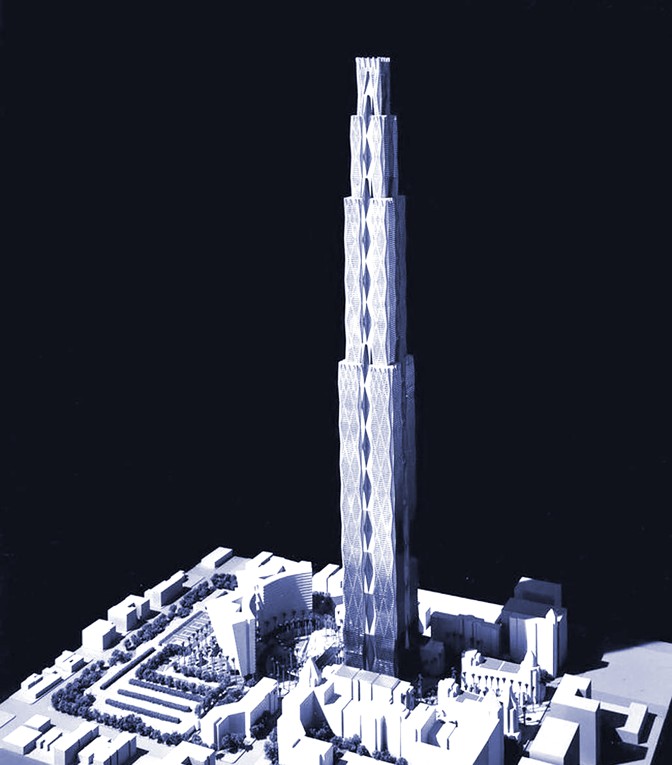

In 1996, the New York Stock Exchange announced that it was considering a move from its historic (that is, outdated) building on Wall Street. Trump stepped in with a proposal for a record-setting 140-story headquarters on more or less the same East River site he had pitched for a world’s tallest building in 1984. But this time, the developer’s plan—with its painterly rendering of a beveled tower not unlike what was eventually built as One World Trade Center—barely stirred a breeze in the press. Perhaps Trump had as little credit with the media as he did with, well, creditors. His dream of erecting the world’s tallest building was, for all intents and purposes, dead. He would have to find another way to get his name into history books.

This article appears in the April 2019 print edition with the headline “It’s Gonna Be Huge.”

* This article was originally published here

No comments